Making Eyes on the Prize: Where It All Began

Callie Crossley

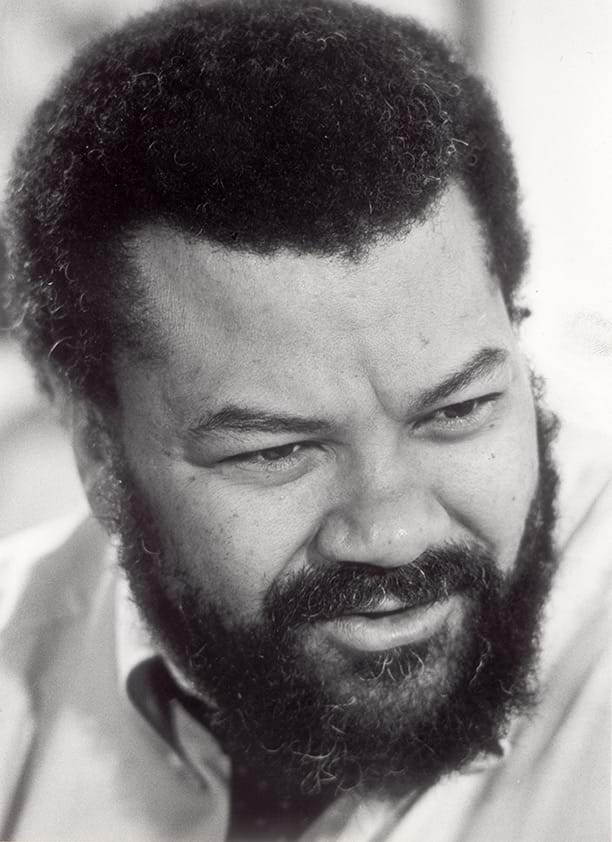

Henry was a very soft-spoken guy, what we call in the South a “steel magnolia.”

Kenn Rabin

He was a father figure, and he was the engine of the project spiritually and emotionally.

Andrea Taylor

His weapon was storytelling and helping communities to heal, bringing their stories forward, being a champion for ordinary people and the power that ordinary people can bring to bear on their own situation and, ultimately, transforming the community and the nation around that.

Judith Vecchione

Henry was a force. He was clearly very, very smart, very committed, knew the stories, knew the people. He listened very hard to people, and he adapted and gave you a lot of freedom where he could.

Laurie Kahn

He had a really strong belief that what we were doing really mattered to the nation. We all got that sense of mission from Henry, also his passion for telling the stories of ordinary people—the foot soldiers of history—not just the leaders. That was contagious.

Jon Else

Henry Hampton was a passionate African American activist. That was sometimes at war with his passion to be a sober African American journalist. Henry was schooled by Jesuits. He went to a Jesuit high school. The Jesuits are skeptics, the gentlemen scholars of Catholicism. That lived on in Henry.

Judy Richardson

He cared so much about the material, it would take him forever to make decisions.

Callie Crossley

He was charming; stubborn—sometimes I think unnecessarily so—generous; bright, bright, bright. He had a charisma about him that made it possible for him to go raise money in these little clumps and in big sums, from people you never would have thought would have given him any money. He was fearless about that.

Jon Else

He would treat everyone in the room as his intellectual peer or his intellectual superior, even though he was always the smartest guy in the room. He would talk very softly so people would have to lean in to pay attention. He spoke with tremendous authority. He had grown up in segregated St. Louis, Missouri. He had worked with CORE, he had been in sit-in demonstrations in St. Louis. He had gone to Selma. He had marched with King. He had spent many years doing the preliminary work for Eyes on the Prize.

Kenn Rabin

He would give a speech about what the project was and what it meant to him and how he had marched in Selma as a teenager with polio and how the Emmett Till story affected his life. His personal journey. People would just sign on. He was probably the best fundraiser I’ve ever seen, even though he always needed money.

Henry Hampton ran Blackside from a rambling house on Boston’s Shawmut Avenue. He began filling it with staff. Though many of them came from WGBH, Boston’s public television station, each of the young producers, researchers, and members of the camera crew who grew to share Henry Hampton’s vision brought their own set of skills and experiences to the project. Hampton had a unique ability to recognize their potential.

Orlando Bagwell

I had been ordering documentary films to show members of my New Hampshire CYO [Catholic Youth Organization]. This was in the period when the Black Panther Party had become a public information space. I found the conversation around these documentaries exciting, so I changed my major to film.

Jon Else

When I came of age during the 1960s, there was a tremendous amount of social unrest in this country. I didn’t have the stomach for it. I couldn’t navigate between the demonstrators and the cops and the tear gas. So I took a job in a film processing lab. I was able to watch the same film over and over and over, maybe a hundred times. I thought: You know, I could do this better than these guys. So I went to film school.

Louis Massiah

I’d been working at [New York’s PBS station] WNET, writing interstitials and producing short science news segments. My training was in astronomy and physics. I had decided to go to MIT graduate school because they were trying to develop the technological arts and at that time MIT had a very, very strong documentary film program.

Callie Crossley

I was in local television. Television was very comfortable to me, but it didn’t feel like a permanent thing.

Cara Mertes

Public television came out of the failure of the commercial systems to deliver information, education, science, a whole range of media experiences, news. So the idea that every person in this country should have access to trusted information and high-quality programming was what drove the invention of the public media system. We needed a system that was not beholden to the marketplace. Likewise, we needed content that was created by artists who were interested in telling the stories.

Kenn Rabin

The Television Laboratory [at WNET] was involved with independent video makers who were carving the path toward using video as a way to express things the way artists did. We had a local show on once a week that showcased abstract expressionism but in video. The department began to give grants to some of these artists to do their work. We financed people who’ve since become notable. We funded Errol Morris’s second film. I had to round up 35mm projectors to screen it, because all he could give us was the 35mm print.

Jon Else

I went to film school at Stanford. I started out trying to work in feature films, narrative filmmaking. That was just—oh, it was awful. I finally, finally realized that documentary was all I wanted to do. I started out doing medical documentaries.

Judith Vecchione

After college, I spent the summer as a vacation replacement at WGBH [the PBS station in Boston]. From there I went into the captioning department, to NOVA as a post-production assistant, and then to the predecessor of WORLD. When Vietnam came up, I got hired as an associate producer. There were a lot of opportunities, and I was, as they say, one that could jump when needed. I wasn’t a soldier in Vietnam. I wasn’t a black person being denied my civil rights. But I was aware of them as stories that needed to be told and explored.

Laurie Kahn

I was teaching philosophy and sidling into filmmaking. The producers at WGBH interviewed me three times. Finally, they said, “We don’t know what to do with you; you’re overeducated and underqualified.” I volunteered to be an intern. Judith Vecchione realized that I knew my way around the library. One of the producers had an associate producer who left to go to law school with no notice. Judith said, “Well, Laurie doesn’t have a lot of experience, but she is a fast learner.” So I became an associate producer.

Judy Richardson

My best friend, Nina Hayes, she knew film, and she knew Henry. Henry knew I had no experience, but he assumed I also knew the [civil rights] movement enough that I could hit the ground running. I was the only employee for the first six months. Henry said, “You will have to be the receptionist, because that’s the only way I can pay you.” Later I became associate producer.

Sheila Curran Bernard

Henry made it his mission to give people breaks, reportedly hiring on the basis of skills and potential rather than seasoned résumés, and I was among many to benefit from that.

Laurie Kahn

Henry had been at work on Eyes on the Prize for quite a while. But this was the first time he had a team that could pull it off, and the world had changed enough that I think he had a better chance of getting funded.

Orlando Bagwell

I had made a few films and was working as a cameraman and editor with Henry Hampton. Then I was recruited to come to LA. For almost two years, I shot dramas and music videos for a living. And then out of nowhere I got a call from Henry, and he said he had gotten the funding for Eyes on the Prize and would I come back to Boston? I did, and it was the most important decision my family and I made.

Judith Vecchione

I didn’t have a mortgage, and I didn’t have a family. I went to WGBH and I said, “I’m going to take this job.” I said I wanted a leave of absence to do it for a year. They said, we give a leave of absence for maybe four or six months and that’s it. I said, “Well, I’ll take that, and we’ll deal with it when we get there.”

Jon Else

Those of us who went there, I think we all understood that this was something way out of the ordinary. This was not like any other nonfiction operation. Henry Hampton was not like any other executive producer. There was a way of doing things at Blackside that was utterly unique in the documentary world.

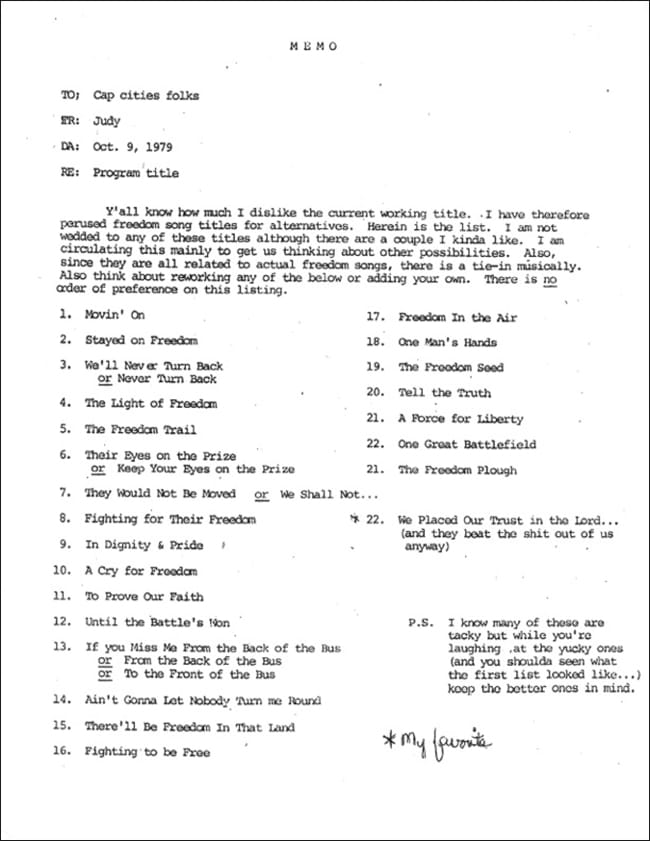

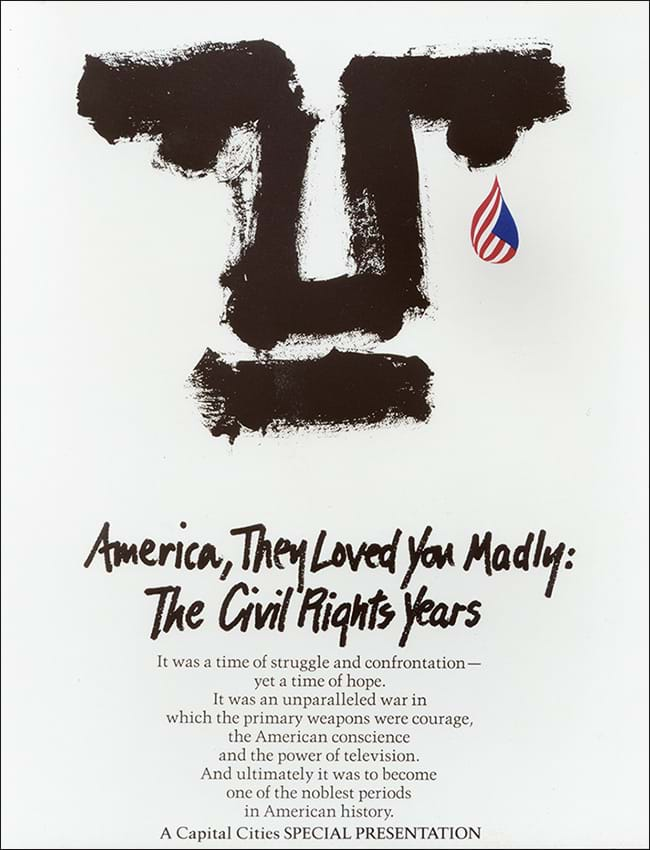

In 1979, Henry Hampton contracted with Capitol Cities Communications, a nationwide media corporation, to create a 26-part series of half-hour episodes that would tell the history of the civil rights movement. He called it America, They Loved You Madly, after Duke Ellington’s favorite farewell salute. He and a small team gathered interviews and archival footage, but when Cap Cities representatives saw their early rough cuts, they were not impressed. The partnership quickly ended, and it appeared that Henry Hampton’s chance to create an epic civil rights film was finished.

Jon Else

In his first attempt to do Eyes on the Prize for commercial television back in 1978, Henry failed miserably. He rebooted the project in ’83, ’84. He was able to raise a little bit of foundation money, and he got a little bit of money from various individual backers in Boston. A guy named Madison Davis Lacy was one of the few African American executives inside PBS; at the time, he was at WGBH. Madison described taking Henry to the Ford Foundation headquarters—a very, very imposing piece of real estate in the middle of Manhattan at the very, very seat of American power. Davis saw that Henry, the consummate outsider, really should be the consummate insider. That was the beginning of the relationship with the Ford Foundation. Ford understood that this series would be contentious. They understood that Eyes on the Prize had to become unassailable journalistically, historically, academically. Ford was also active in funding very, very early voter education projects in the Deep South. They were not newcomers to the civil rights movement.