Making Eyes on the Prize: In the Public Eye

The first six episodes, Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years (1954-1965), aired on PBS in January and February 1987. “The nobility of America’s civil-rights struggle comes through with the directness of a spiritual,” wrote television reviewer Walter Goodman in the New York Times.

Elizabeth Alexander

At the time that Eyes on the Prize was made, black rights, black history, black culture had not been funded and supported and seen as something that was deserving of epic treatment. It was big news when the series was made, because nothing like it had existed before.

Callie Crossley

We started doing some small screenings around Boston. I thought people would like it, but I wasn’t prepared. And then it just started building from there. I realized, Oh, this is going to be something!

Louis Massiah

I had attended the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar [in New York], and Henry Hampton was there. He had shared a rough cut of the Pettus Bridge episode that Callie Crossley and Jim DeVinney produced. It was absolutely remarkable. Very powerful. This was the mid-1980s, amid the Reagan administration’s official erasure or obfuscation of what the civil rights movement was and what its goals were.

Kenn Rabin

By the time Eyes I was halfway through its broadcast, it was quite clear that we had created something that people thought was extraordinary. It woke people up. I remember thinking we were going to have trouble, because we’d only cleared rights to everything for 10 years. This was going to be a series that would come back again and again, and never be out of date.

Henry Hampton had never envisioned telling a civil rights story that ended in 1965. The success of the first six episodes brought the Ford Foundation and other funders back to Blackside. Many of the producers who had worked on Eyes I had moved on to new projects, so Henry moved quickly to get new teams in place to produce a follow-up series, Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads (1965-1985).

Andrea Taylor

Ford was looking at its media program investments and had already put a fair amount of money into Eyes on the Prize, Part I. People around me were, I think, surprised by the impact of the series on viewers and on the process of teaching and learning, and the discussions about race and society and diversity. The foundation was thinking about whether they should fund the second half of the series. How could they use that funding investment to again enhance teaching and learning? Discussions about race and difference? They wanted me to spend some time with Blackside.

Sheila Curran Bernard

Sometime around the start of making Eyes II, Henry gave each of the producers a copy of Barbara Tuchman’s Practicing History, a series of essays, and he inscribed each one personally. It was really special, and a somewhat daunting call to excellence. I think we were aware of how much pressure he was under.

Louis Massiah

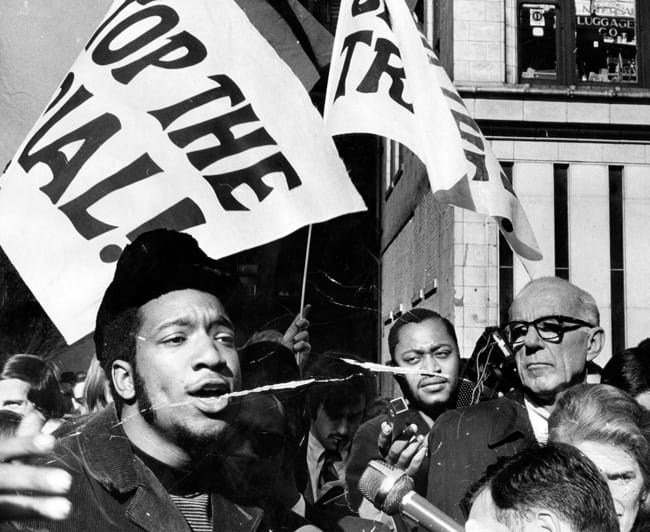

Because of the history that we were covering with the second series, there was more internal struggle. For Eyes I, when you have Bull Connor and George Wallace on one side versus nonviolent demonstrators on the other side, most of the archival footage and most of the national media are on the side of people fighting for civil rights. For Eyes II, we are talking about Malcolm X. We are talking about the Panthers. We are talking about uprisings.

Carla Mertes

Eyes on the Prize II was even more contentious and more difficult to fund because of the content in it, more highly political.

Sheila Curran Bernard

By then, many people knew what Blackside was, and the production of that first series had set clearly established standards for storytelling, research, and accuracy. To some extent, I think that helped to open the doors to research and access, because we could be trusted to be fair.

Eyes on the Prize II episode “A Nation of Law?” told the story of the killing of a young, charismatic leader of the Black Panther Party in Chicago, Fred Hampton. Photos show Hampton before the deadly raid, as well as memorials and rallies following the killing.

Judith Vecchione

Eyes II was really new material. It had gray areas between history and current events. I think we found the stories that were being told in Eyes II were difficult emotionally. Poverty and black crime and black power. All these things were messier.

Sheila Curan Bernard

Attention to the needs of the series as a whole led to a shift in one of our stories. “Ain’t Gonna Shuffle No More” is about rising black consciousness, and we had filmed three stories: Cassius Clay becoming Muhammad Ali and taking a stand against the Vietnam War; students at Howard University in 1968 demanding that the curriculum and administration reflect their lives and history as black Americans; and the prison uprising at Attica, in 1971. At a screening of the edited episode in progress, it became clear that the devastating ending of the Attica story—43 deaths, 39 by the police—appearing at the end of the hour, undermined the episode as a whole. Further, it was clear that the history of Attica worked better thematically in the following episode, “A Nation of Law?” by Terry Kay Rockefeller, Thomas Ott, and Louis Massiah—and that the story they’d filmed about the first National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, in 1972, would work well as a cap to our episode. As an aside, Sam’s interview with Frank “Big Black” Smith in the Attica story is one of the most powerful interviews of the series, in my view.

Louis Massiah

Henry wanted to make a series that was going to interest white viewers. Because of that concern for white middle America audiences, the story of Angela Davis is not in Eyes II. As producers, we wanted her story in the episode, but we lost that battle. I had to tell Angela, “Henry thought a full telling of your story was just too much for the series.” And she said, “There were so few clear victories in that time. It’s not that I’m an egotist, but that was a victory. And we need to tell those stories. My acquittal was a victory against the oppression.”

Andrea Taylor

In the mid- to late ’80s, media was not taken seriously. Serious information, scholarly information, quality information—there were certain instruments and vehicles for disseminating that kind of information, and television and film were not at the top of that list. Ford would give a grant to examine, say, reproductive health or education policy. The grantee would turn in the report to the foundation, and maybe 20 or 30 people might read it. Then Eyes came around. You got voices that you’ve never seen, faces that you’ve never seen and heard. The power of that versus a 30-page monologue about diversity or immigration or segregation … You see what I’m saying?

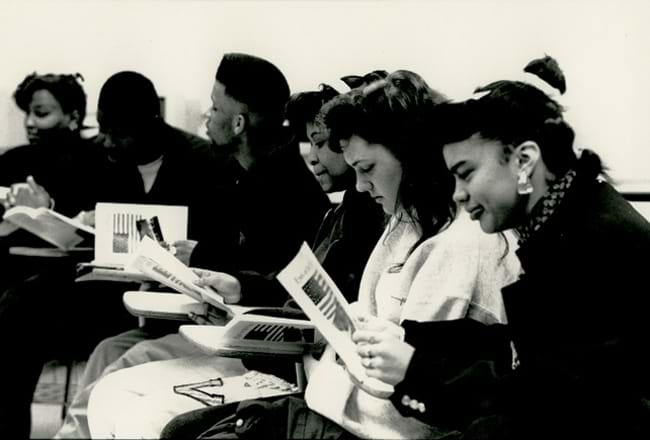

Eyes on the Prize presented history in a way that connected with students. Recognizing this, history teachers around the nation began using it in their classrooms, showing kids an arresting account of the past that reshaped how a generation of students understood recent American history.

Lyric Cabral

I believe I saw Eyes on the Prize in a history class when I was around 10 years old. We watched the episodes over a week, and I remember writing some essays. I think the most arresting footage was that of the children, the boycott, the children getting thrown in jail. That resonated with me. I remember the images of Selma, the crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, because there were young people present. The images of young people getting hosed and getting bit by dogs. They represented me.

Elizabeth Alexander

I have been an educator at the university level for most of my career. I started using the series as required viewing for students when I taught classes on African American literature and culture in the second part of the 20th century. I would always assign them to watch Eyes on the Prize on their own so that they could put the culture that we were studying on a historical timeline. No one had a laptop. You had to go to the film study center. You had to reserve a booth. You had to reserve a time. I would often arrange for them to be screened, but students had to make an effort. What’s so dramatically beautiful about the series is that we finish one episode and you can’t wait to see what happens next.

Sheila Curran Bernard

I teach a course called Civil Rights: A Documentary Approach. Each week, in addition to assigned reading, viewing, and discussion on civil rights history, students meet in the class and together watch an episode of Eyes on the Prize. I did this to minimize the kind of distracted, multitasking viewing that we’re all guilty of; students have no choice but to settle in to the pace of the storytelling that may, at first, seem outdated. And it works. They get drawn into the historical stories, emotionally as well as intellectually, and later draw powerful connections to issues and individuals in the present day, from challenges to voting rights and gay marriage to the Black Lives Matter movement and prison-industrial complex.

Lyric Cabral

I went to a predominantly white private school, one of four black students. I was aware of race, but Eyes on the Prize helped me to understand some of the personal things I was starting to see. It offered me context.

Elizabeth Alexander

I would sometimes focus on the episode where we see Emmett Till’s funeral. I would always tell the students that collectively we were about to bear witness to something horrifying that they have not had an opportunity to see before. Bearing witness in the way that people in the time that Emmett Till was lynched did, looking at the picture of his body in the open casket in Jet magazine. That it was an important way to understand not only what happened but to understand the impact of what happened, to understand what racial violence really does to people. Bearing witness calls a viewer to understanding and moral action. You cannot unsee that image.

Elizabeth Alexander

There are sometimes these cultural spaces, these collectives where there is leadership and opportunity and serendipity that gathers together the best of the best. I think the legacy is not just in Eyes itself, but in the careers the Blackside filmmakers went on to have.

Jon Else

One of the great legacies of Henry Hampton is this giant, vibrant community of young filmmakers of color in America.

Judith Vecchione

I ran a workshop for PBS producers, and I just concluded a yearlong training series to draw in people from underrepresented groups—to bring in perspectives from different races, genders, a range of locations and experiences.

Orlando Bagwell

While at Blackside, I decided I would be a director and focus on story. Best move in my life.

Callie Crossley

After I left Blackside, I went to ABC News 20/20, and we did mini-documentaries. My normal piece for 20/20 is 14 minutes. Without Blackside, there was no way I could have gone from commercial news to 14-minute stories.

Laurie Kahn

After American Experience, I jumped to making films as an independent producer. My films have all been about the lives of extraordinary, ordinary women, that notion of telling history from the bottom up rather than the top down. I was interested in examining the ordinary people who lived through times of huge change.

Sue Williams

I started my own company in 1986 or ’87 to do a series of films about China. We didn’t have the money to do school the way Eyes did, but we always had a team of historians and advisers. That kind of intellectual rigor, it did make a big impression.

Elizabeth Alexander

I’m sure there are many filmmakers who were not associated with Blackside who saw that it could be done and who saw a standard of excellence and felt that it was possible for them to work in that mode as well.

Jon Else

Our great mentor, Vincent Harding, said that these stories have to be told anew every generation by new storytellers.

Lyric Cabral

The goal of my documentary [(T)error] was to expose issues that I think are in need of change, and that are not necessarily highlighted in the mainstream media. Typically, I report on the intersections of national security, civil rights, race. So I’m focusing on how surveillance policies and maximum security policies impact black Muslim communities. When 9/11 happened, I was in my freshman year of college. I saw the impact on my community immediately. I saw the ripples of fear. I saw a lot of sensationalism and inaccurate portrayals of my community. I realized I could offer an alternate representation of people who were being charged with crimes of terrorism or communities who were living under this cloud of suspicion. I began to photograph the family members of people who had been accused of national security crimes. That was what I did from 2001 until 2010, when I began filming.

Carla Mertes

The independent media scene grew up alongside public media, and Ford was funding both. In coming to JustFilms, I’ve been able to look at that history and the resources that went into both building the structure and an independent media field that supports the artist and the content and really think about what we do in the next stage, in the 21st century, with this incredible legacy—an incredibly vibrant, global, independent media community.

Lyric Cabral

(T)error is the first film to document an active FBI counterterrorism sting operation. Our main character was a former Black Panther turned FBI informant. In July 2014, we went to the Edit Lab; the Sundance Institute pairs you with editing mentors handpicked to help you shape your story. One of the people that Sundance picked to consult with us was Jon Else.

Lyric Cabral, filmmaker of (T)error, talks about the lasting impact of Eyes on the Prize on documentary filmmaking, and advice from Jon Else on interviewing sensitive subjects.

Jon Else

Eyes on the Prize is an operating manual for the expansion of democracy.

Kenn Rabin

I think it made white people much more aware of the civil rights movement. Even if it was 30 years ago now, I don’t think anyone who ever saw Eyes won’t know who John Lewis is.