“The biggest barriers are prejudice and fear.”

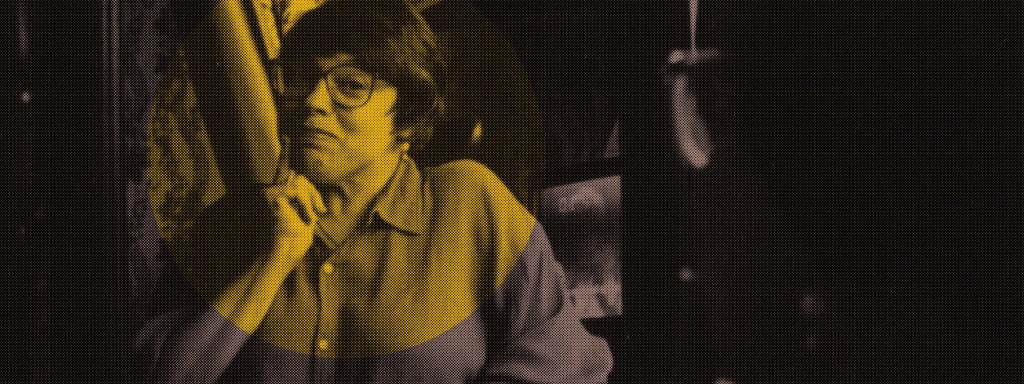

That’s just one of the many pieces of wisdom Judy Heumann has imparted upon me over our three years of friendship.

Being disabled, I’ve always carried a certain level of shame. Shame for being seen as disabled walking down the street everyday with one significantly shorter leg. Shame for being judged as less than. And shame for not being able to do everything a “normal” person can.

But Judy, a longtime champion of disability rights who was paralyzed from polio at 18 months old, helped me confront all of that.

We met three years ago when Judy became a Ford Senior Fellow helping the foundation shape its work on disability inclusion. At the time, President Darren Walker was called out for excluding disability in the foundation’s new mission to combat inequality. It was a big learning moment for everyone at Ford.

I admired how she would roll into meetings with such spunk, always wearing her activist hat to challenge the status quo, teach, and advocate for inclusion.

As I got to know Judy, I learned she is much more than just a disability justice leader. She is a world traveler, a teacher, an author and, to me, a mentor, a friend, and a role model. Our conversations, though work-related, were always personal.

Like the foundation, I, too, had a lot to learn. At the time, I wasn’t connected to the disability community, despite years working on human rights. Disability, especially mine, was a topic I had always felt uncomfortable addressing publicly.

Judy always said to me, “I never wished I didn’t have a disability.” But she, like many disabled people, has had to confront shame.

In our conversations about shame, she used her vibrant life experience—her personal and political struggles and victories, her journey of self-reflection and learning—to help me deconstruct and make sense of my disability. She taught me how to own my disability, to be proud of it, and to accept it as a part of life. It’s a process I’m still working on.

Now, Judy’s story and endless sagacity can touch more people, both with and without disabilities, with a new memoir published this week. In Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist, she tells her story of fighting for the right to access an education, to secure a job, and to just be human.

In honor of her book and her life’s work, we sat down with Judy to ask her a few questions about her journey as an activist, the challenges still facing the disabled community and what brings her hope.

The first line in your book is something you have told me repeatedly: I never wished I didn’t have a disability. How has your disability shaped you and the work that you do?

I had polio when I was 18 months old. My life has always been as a disabled person. Like the color or my eyes or the color of my hair, it is a part of who I am.

As I got older, I began to learn that other people saw my life as a tragedy. They would say things like, “Isn’t it a shame. Look at what she could have done, what she could have been if she could walk and be more independent. It would have been so much easier for her parents.”

This type of language wasn’t initially clear to me as a child. However, over time it had a mounting impact on my life. I grew to feel confused, guilty about what my parents had to do for me and how it took time away from my brothers, and acutely aware that I was different.

I simply didn’t meet other people like myself on a daily basis. I didn’t really begin to have friends with disabilities until I went to Health Conservation 21, a special education class for people who cannot walk up the stairs, when I was nine years old. Over the years, as I became friends with other disabled people and we shared our common stories, we began to see that we had to stop feeling guilty about who we were. We needed to take back our lives, create the lives we wanted to lead, and demand that society make changes that would enable us to live our lives as we wished. We had a right to feel angry, but we needed to take this anger and work on the changes we wanted.

People saw walking, hearing, seeing, talking, and processing information in a typical way as being the most important—and, to a large extent, that’s still the case. Non-disabled people wanted us to be shaped in their image. Instead, we began to think about the world as we believed it should be. We saw—and still see—that the ways we do and want to do things strengthens society. As we gained confidence in who we were and in what we wanted and believed in, we became empowered and confident.

As I gained self-confidence in who I am and others gain their self-confidence as disabled people, we are reaching out to more people with disabilities to help them recognize that they are not the problem. What we are demanding are slowly producing changes here in the US and abroad. Barriers are not just physical; the biggest barriers are prejudice and fear.

I personally have found that I must speak what I believe and feel. Speaking about oppression and discrimination is hard to do, and many people have difficulty listening and looking at what role they play in allowing discrimination to continue. But ableism, racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination will only end when we, as a society, hold ourselves accountable and no longer make excuses that condone past and current practices. On a daily basis, I try to be aware and take action to make changes in my life that advance justice and equity for all people.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

How did you become a justice leader? Tell us the story of the moment when you realized you have to champion issues you care about or affect you?

There was never one specific moment when I realized I had to champion issues. There were many moments when I felt I needed to speak out on my behalf or on the behalf of others. In some cases, I spoke up. Other times, I cowered away.

For instance, the day I graduated from high school, I was to receive an award but the principal said my father was not to pull my wheelchair up on the stage to join the other award-winners. Instead, I was to sit in the front row and the principal would come to the edge of the stage and hand me my award. I was mortified, trying not to cry. My father pulled me in my wheelchair up to the steps, saying I needed to be on stage. In the end, I had to sit in the back row but I made it onto that stage.

There are myriad other examples that I and millions of others like me could—and should—tell to allow people to understand the pain we have faced.

For me, the accumulation of these experiences came to a crescendo when I was denied my teaching license in the 1970s. I knew for many years that if I pursued a career as a public school teacher, it was likely to be a battle.

I took the courses I needed and, although I had no formal teacher training in the classroom, I sought opportunities to teach children in after-school programs and through tutoring. Yet when I was finally denied my license because of “paralysis of both lower extremities because of poliomyelitis,” I was a bit frozen.

I thought, “What do I do?” Should I take action or just speak about the denial? Should I give up or fight, not knowing what that would like? I spoke to family and friends to give me courage and gained the inner strength I needed to take action. But we had no NAACPs or other organizations to support people in the disability arena. We had no organizations with lawyers who could represent us.

I suppose it was fate, plus family and disabled friends, who made me recognize that pursuing my teaching license was bigger than me and bigger than being a teacher.

A serendipitous phone call I received from Roy Lucas, an attorney writing a book on civil rights who had questions about my situation,made my lawsuit a reality when he and one of my father’s customers, Mr. Schwartzbard, agreed to take my case. Justice Constance Baker Motley, the first African American woman appointed to the Federal District Court, made it possible for me to finally get my teaching license and become the first wheelchair rider to ever teach in a New York City school. I will always be thankful that my family and circle of disability rights colleagues gave me the courage to fight.

From your role in the Section 504 sit-in in 1977, as hilariously covered by Drunk History, to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, what were the biggest lessons you learned about how change happens?

Change doesn’t happen overnight. It necessitates the ability to articulate the problems and the solutions you believe should be implemented. It requires the ability to articulate the impact of the discrimination, and the effect of your proposed changes.

During the fight for the ADA, the disability community learned that, while specific remedies might be different depending upon an individual’s disability, unity across disability groups was paramount. We had to be able to come together and jump across the silos represented by our different types of disability. There are thousands of different disabilities, and they impact people in different ways and at different times in people’s lives. As a community though, we had to be unified and agree that we would throw no one under the bus.

We also needed people who understood the legislative process. The community across had to articulate their personal stories to their Congressional representatives and hold those representatives accountable. We needed to work with the broader civil rights communities, labor unions, religious communities, the women’s movement, mayors, state and local representatives.

The passage and implementation of Section 504 and the ADA took 18 years. These laws would have a sweeping impact across the US, but not overnight. Getting the laws and regulations passed was, of course, only the beginning. Even today, we must persist in ensuring that people continue to learn about the laws, use the laws, and fight for effective implementation.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the ADA. That was a groundbreaking law made possible by the work of thousands of activists over the course of decades, really, centuries. Where do we go from here when it comes to disability rights and inclusion? What gives you hope today?

What gives me hope today is the fact that more people are recognizing that disability is a normal part of life. We should not feel ashamed.

However, we must continue our fight to end marginalization and exclusion from education, employment, and our society more broadly. We need to remain active to ensure that the laws we have fought so hard for are implemented, including through strengthening of funding at the federal, state, and local levels of government.

Media in all its forms, while slowly improving, has yet to adequately reflect disabled people and our lived experiences. Knowledge of how disability impacts the news stories being told is limited. Television, streaming, documentaries, and advertising still do not reflect disability in an authentic way. Disabled people are still usually played by nondisabled people, and most of those roles are of white disabled people. This failure continues to perpetuate the old views of who we are, what we experience, and what our dreams and aspirations are. As a community, we continue to be largely out of sight and out of mind. Society must take responsibility to work with us, and ensure that the media more accurately represents us.

The private philanthropic community must play a more active role. We need to empower people of all ages to be able to receive support and services to help them remain in their homes. We need to continue to be a part of the national movement to guarantee that all people have access to health care, and that those who need various forms of assistive technology—hearing aids, wheelchairs, glasses, etc.—can get it easily and affordably.

We need to continue to organize. We need to ensure that the diversity of our movement —be that in terms of disability, race, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, national origin, etc.—is truly represented and that all people across our communities benefit.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

You were pivotal in shaping the Ford Foundation’s work on disability inclusion as a Senior Fellow. What were the biggest takeaways from this experience? And what are the opportunities philanthropy and other funders can embrace to advance disability inclusion?

The foundation has committed itself to inclusion of disability in its work. It has recognized the importance of understanding how and why disability was not previously included and is working with the disability community to learn what it needs to do. Of great importance to me is that this is an organization that values learning, and now disability is part of that learning. Senior leadership and staff are learning why the inclusion of disability is important for Ford to achieve its mission and acting accordingly.

The Ford Foundation’s motto—we believe in the inherent dignity of all people—is finally becoming a reality.

The foundation has reached out to others in philanthropy to challenge them to be inclusive. It is bringing attention to organizations of disabled people of color. It is slowly playing a major role in a way that should have lasting impact, not just in philanthropy but across society.

While there is much more to do and the need for continued urgency, I believe more people now understand what to do and why they cannot turn back.

What do you hope to achieve with your memoir? Why share your story in this form now?

For me, the writing of this memoir with Kristen Joiner, has been an important part of my journey in life. First, it has enabled me to put on paper what many have been asking me to do for a long time. I hope that my memoir will encourage other people,with and without disabilities, to tell stories of how prejudice and discrimination have impacted their lives. I hope it will embolden them to speak up and fight, not only for their own rights, but to work with others to obtain justice and equality for all.

I want others to tell their stories, so that we understand that the discrimination I have faced is not so unique, and that there are others who have faced and continue to face even more heinous discrimination.

I want people to dig down deep and look at which changes each one of us needs to make to improve our society.

I am proud that our community of leaders is growing and broadening. We are forcing discussions that have not happened before. We are learning that we have a responsibility not only for our lives, but for the lives of others.

We have a responsibility to participate in all aspects of society. Registering people to vote and ensuring that all people are given the opportunity to participate in all facets of political life must be a part of our agenda.

I hope that this memoir spurs others to write and to use social media to get out their stories. Of equal importance, I want the media to see that there are rich stories out there that must be told.